[Some computers might ask you to allow the music to play on this page]

Geri Allen (1957 - 2017)Six Examples Of A Maestroby Steve Day |

'Full Focus' is a series where musicians and others discuss a jazz track or tracks in detail. The idea is that you are able to listen to the track that is discussed as you read about it. If you have a track on an album that you have released you might like to share the ideas behind it and describe how things developed - if so please contact us.

This month, Steve Day considers six examples of music that for him define the late pianist, Geri Allen. Contact us if Steve's examples ring true for you, or if there are other examples you think should be considered.

.................................................

Back in June, I received an email from Ann Braithwaite out in Lincoln, Massachusetts; it was my first news that Geri Allen had died. I should know by now that most of us leave this planet in circumstances not of our own choosing. In her case, only fifteen days past the passing of her 60th birthday. All these years of listening to the music of the great Geri Allen weren’t suppose to end like this.

I’d been hooked from the beginning. She is/was (it’s like that, the terrible enactment of the past tense) amongst the most deftly fluid pianists I have ever encountered; expressive to the point of poignancy on inner celebration. Geri Allen probed with poise, a certain, a very certain, pressured touch. She was definite and precise yet initially she could ring faint until your ear caught the subtlety of the angle. Like catching stars, the flame flickers, the light hovers but doesn’t disappear; it was a sound that was all her own. Some people tried to label her (it’s easy shorthand, saves on description) as ‘mainstream’, next year ‘fusion’, then ‘avant-garde’ – Geri Allen picked up more definitions than a dictionary. The truth is she embraced it all, took in everything, but always came out as Geri Allen.

Back in 1998 I wrote the following words, describing a concert I’d seen/heard at Cheltenham Town Hall – the classic line-up, Geri Allen, piano, Charlie Haden, double bass and Paul Motian, drums:

“The first notes she played she hardly played at all. It was as if she stoked the notes from the piano interior in order to encourage them to be heard.....The whole trio is one of economy and careful use of the volume dynamic. I have this visual image of seeing Charlie  Haden rocking his double bass from side to side as if trying to bear down on the light blue lines that spiralled out from the piano. Geri Allen takes her time. Even when she’s playing a fast line, there is never any impression of hurry. Watching her play it is easy to think the person does not represent the sound; unless her hands are visible, it is as if she is merely sat at the piano. Occasionally she glanced across at Paul Motian, but her posture was very still, yet from this quiet person came an improvisation that stood time and space on its head.” (Two Full Ears – Listening To Improvised Music (Soundworld).

Haden rocking his double bass from side to side as if trying to bear down on the light blue lines that spiralled out from the piano. Geri Allen takes her time. Even when she’s playing a fast line, there is never any impression of hurry. Watching her play it is easy to think the person does not represent the sound; unless her hands are visible, it is as if she is merely sat at the piano. Occasionally she glanced across at Paul Motian, but her posture was very still, yet from this quiet person came an improvisation that stood time and space on its head.” (Two Full Ears – Listening To Improvised Music (Soundworld).

Charlie Haden, Paul Motian and Geri Allen

You see, for me, Geri Allen has been one of the very great pianists of the last thirty years, a true maestro. Read what a lot of the blogs and websites are putting out and you’d think she was an academic. And on one level she was. Perhaps we all are to some degree (sic). But first and foremost Geri Allen was an extraordinarily creative pianist and she came from a long line of jazz pianists – nobody knew her own history better than Geri Allen. So start talking about The Nurturer and the conversation has to include Lil Hardin, Thelonious Monk, Mary Lou Williams, Bud Powell, you’ve got to get right in there with Andrew Hill and Cecil Taylor, Paul Bley and then back again to people like Lennie Tristano, then Herbie Nichols and Red Garland, okay, and Bill Evans. But with Geri Allen you’ve also got to travel past all those important ebony and ivory people. With certainty she was Michigan and Motor-City, M-Base and Ornette; she could be free-fall and stride, she could be seriously funky, and as pastoral as springtime.

Geri Allen understood horns and reeds – what they need, how they blow, yet she should could ‘space’ a piano trio into places of contemplation to the point where she was hitting on the sacred. In my opinion, Geri Allen was badly underestimated, particularly in Europe. Grasp the implications of her early 1990’s work with Jack DeJohnette and Dave Holland. Together they produced The Life Of Song, an album for Telarc which crossed over so many times, the weave of music is truly boggling. Her composition Holdin’ Court is a good example; the piano is bravura central, almost an investigation, and you can hear Jack DeJohnette rippling the balance throughout and Mr Holland constantly feeding the situation with power-play. Such empathetic understanding is also present on the work the three did with the singer, Betty Carter on the Feed The Fire tour/album. I’m talking something exceptionally profound. Scat song and a personalised piano held within what is in effect, the avant-garde of the Miles Davis ‘Lost’ quartet rhythm section.

My intention is to take six specific performances which, I contend, demonstratively prove such profundity – in all its joyful exuberance and grace.

Charlie Haden’s first recorded performance of Lonely Woman was on 22nd May 1959 for Ornette Coleman’s debut on the Atlantic label, The Shape Of Jazz To Come. In his lifetime Mr Haden went on to record the Coleman composition numerous times with different line-ups. Why wouldn’t he? Lonely Woman is a special melody line that breaks poignancy into gaping wide moments of pure solitude (if you know what I mean). There’s a good argument for making the case that the version on the Etudes trio album, with Haden, Paul Motian and Geri Allen, recorded 28 years after The Shape Of Jazz To Come, was among the finest, richest, most sublime readings of this great tune. There’s a measured bass led intro, then Geri Allen picks up the melody and carries it directly into a collective infinity. She never hurries herself or Haden and Motian; this is all balance and a light grandeur containing depth and deliberation. The ability to play the written line, then displace it, rebuild it, soften the sequence and then pass it back to Charlie Haden as if it were a precious gift. And by any stretch of the critique, that is exactly what the Geri Allen performance of Lonely Woman was. A precious gift.

Geri Allen (piano), Charlie Haden (bass), Paul Motian (drums), 1989 Lonely Woman, from Etudes

It’s a long time ago now, but I remember buying The Nurturer CD in Mike’s Music Matters jazz shop in Bath. I was fingering through the racks and found the disk; because ‘Allen’ is at the beginning of the alphabet it was also near the counter. I passed the disk straight to Mike and he immediately put it on the shop stereo. For some reason Mike played Batista’s Groove first (it’s the fourth track on the disk). The B Groove begins with a Jeff Watts/Eli Fountain percussion break over which a Kenny Garrett and Marcus Belgrave horn conversation hurls the thing forward exchanging lines like twins swapping stories. The whole track is only a little over five minutes in length. Geri Allen herself doesn’t enter until roughly half way through, taking over ‘the groove’, and in the course of just under a minute and a half, utterly defining the time it takes to cause a commotion. My memory is that there were a couple of other punters in the shop that afternoon beside me. Everyone began shuffling around, dancing on the spot to Batista’s Groove, with Mike conducting an instant quiz as to which instrument was being played by the leader of the band? See, in Geri Allen’s short interlude of a solo she manages to capture the essence of literally hitting-off an acoustic piano statement in the middle of horns and beats. I walked away with The Nurturer in my shopping bag with Mike ordering a couple more copies for other people. There’s a lesson in all this which I’m still learning; it’s not the length of a solo that matters, it’s the content.

Geri Allen (piano), Marcus Begrave (trumpet), Kenny Garrett (alto saxophone), Robert Hurst (bass), Jeff Watts (drums), Eli Fountain (percussion), 1990 Batista’s Groove from The Nurturer.

RTG opens this unique album. The legendary pairing of Ron Carter and Tony Williams set in a stretch of music containing six Allen compositions, two Monk tunes played as one, plus five standards (though not the same old - same old). RTG’s got the piano riff, the keyboard dip and dive into extemporisation, the riveting hammer on wire hit that trips the light fantastic through the middle of an amazing contrapuntal maze; Geri Allen dealing with the great rush of abstraction which is Tony Williams (the Janus-opposite to Paul Motian’s riddle of breaking up rhythm). Hang on round the bends as Williams rides fast high-hat, splash cymbals, drum fills and flips. Then comes Ron Carter counter-lining the piano-drive as if he’s just extended the neck of the double bass. RTG is pop song length (2.45) yet it goes nowhere near popular song performance. RTG is all statement; Ron, Tony, Geri, a mini musical explosion, beautifully controlled and given weight by Geri Allen’s ability to carry a performance higher and higher. This bass/drums team must rank as (one of) the greatest in the jazz dictionary. And it’s got to be said, for all their historical staggering association with the definitive (Miles Davis, Herbie Hancock and Wayne Shorter), the uniqueness that Geri Allen brings to this session means that any serious analysis of Carter/Williams has to incorporate the Twenty-One album. The fact that the recording does not carry the same symbolism as other more well known sessions is nothing to do with lack of quality and everything to do with the glass-ceiling women, as instrumental jazz players, still encounter. We might as well say it here as anywhere else in this retrospective. In Geri Allen’s case it was starkly obvious.

Geri Allen (piano), Ron Carter (bass), Tony Williams (drums), 1994 RTG, from Twenty-One.

This album is one of the real jewels of my wall to wall bank of CD’s. I’ve been playing this Betty Carter led live session at least once a year since 1995. Every track is diamond, I’m All Smiles and Feed The Fire exceptionally so. These are performances that ring the truth of music. The track Feed The Fire is an Allen original, there’s a blast performance with Carter/Williams on Twenty-One, and an often forgotten extended version with Palle Danielsson and Lenny White on Some Aspects Of Water. The latter is such a peach – she was always able to get under Lenny White’s inherent groove and here Palle Danielsson also takes a bass solo that results in the pianist taking herself off down an exploration not found on other versions of the tune. Back to the Betty Carter version – the album was recorded live at the Royal Festival Hall in London, the YouTube version is from the same tour, in Hamburg. Feed The Fire is a great example of a riff at work; the repeated phrase used like a balancing act, offered like a weighted message before plunging into the possibilities. Live, Betty Carter’s diversity of vocal gymnastics are literally pitched, curving into the rolling piano flow. Yet in London, it is Ms Allen’s repetition which sets the scene, and once Carter’s scat vocals start to stretch the scenario the piano is constantly providing two handed comment. Instrumentally, Geri Allen takes the first solo, Dave Holland the second, Jack DeJohnette the third – bass/drums totally in tune, in-hoc, to the keyboard’s design plan. It’s a ten minute-plus workout that feels like the length of song form, such is the empathetic hook and hammer these four musicians bring to the performance.

Betty Carter (voice), Geri Allen (piano), Dave Holland (bass), Jack DeJohnette (drums), live in Hamburg 1993, Feed The Fire.

Seventeen years ago this is what I wrote, reading it again, I don’t need to add anything:

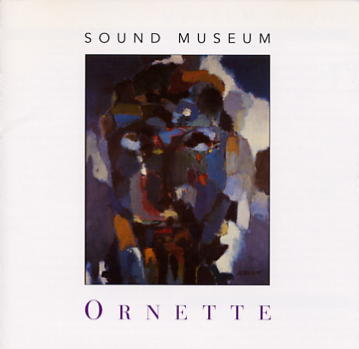

'Even if there is no such thing as god. I guess Ornette Coleman can invent one. Quite where the resurrection of What A Friend We Have In Jesus came from is another steal on my sub-consciousness. What I do know is that this trip with the old and friendly miracle  worker is just what the doctor ordered. It seems to go back a long way. Further back than Ms Allen did in the Robert Altman film Kansas City, further, much further than the bright cities of New York and Los Angeles. Probably the railroad south could be witness to those gospel choruses. Ornette Coleman’s relationship with the membrane of Christianity is, if not a moveable feast, certainly a bite-size break on wheels. I am reminded of Mr Coleman’s past encounters with Jehovah’s very own door-to-door witnesses. There is also a rap track that Prime Time have been gigging with called Bible Talk. Never under-estimate old time religion, it can come creeping up from under the floorboards. On What A Friend We Have In Jesus it is for once a welcome interruption. Ornette Coleman’s alto horn sounds so sorrowful and straight forward, so beautifully cool and plaintive, and mellow, and hungry, yet full of something that is only usually there on his ballads. ‘Friendly Jesus’ rocks along at a good medium pace, with Ms Allen placing out the changes just as if her boss had always known them.

worker is just what the doctor ordered. It seems to go back a long way. Further back than Ms Allen did in the Robert Altman film Kansas City, further, much further than the bright cities of New York and Los Angeles. Probably the railroad south could be witness to those gospel choruses. Ornette Coleman’s relationship with the membrane of Christianity is, if not a moveable feast, certainly a bite-size break on wheels. I am reminded of Mr Coleman’s past encounters with Jehovah’s very own door-to-door witnesses. There is also a rap track that Prime Time have been gigging with called Bible Talk. Never under-estimate old time religion, it can come creeping up from under the floorboards. On What A Friend We Have In Jesus it is for once a welcome interruption. Ornette Coleman’s alto horn sounds so sorrowful and straight forward, so beautifully cool and plaintive, and mellow, and hungry, yet full of something that is only usually there on his ballads. ‘Friendly Jesus’ rocks along at a good medium pace, with Ms Allen placing out the changes just as if her boss had always known them.

The melody is completely re-worked so all that is left is a little turnaround. The piano and alto saxophone groove all the way down the great wide road that leads to innovation and experience. If there needed to be a demonstration as to why Geri Allen works in the context of this Quartet, here it is. The piano rocks with recognition, nods in the direction of Jaki Byard, who in turn is vamping the rhythm with Willie ‘The Lion’ Smith and Mary Lou Williams. Suddenly things are falling in place with both the past and future tense. I find it a startling performance. An honest account of the holy modal rites of passage that have taken jazz from the cradle of New Orleans right through to Chicago and out onto the Western seaboard. In a Sound Museum such things come to light. I think What A Friend is a lovely study of just the way it is; whatever the reason behind its history, the swing with which this performance swings is as free as anything else Mr Coleman has ever set in motion. Ornette Coleman: Music Always (Soundworld)

Ornette Coleman (alto saxophone), Geri Allen (piano), Charnett Moffett (bass), Denardo Coleman (drums), 1996

What A Friend We Have In Jesus (Variation) from Sound Museum, Hidden Man.

This concert goes back to 2001 – it was a stellar line-up. The gig begins with a piece called Miss Jessye (after the opera diva Jessye Norman). The opening ripples with the whole band holding the central spot. John Abercrombie’s guitar counterpointing Charles Lloyd and Geri Allen; Mr Lloyd’s decisively subtle tenor moves through the tune as if signing a signature but its Geri Allen who is the first to go under and out front from the horn. She designs something here which is as much Allen as it is Lloyd. It’s one of her classic performances, she doesn’t take over, yet she seals the deal. Miss Jessye is a Charles Lloyd tune, but in a sensitively reflective manner the pianist almost explains the character of the piece by way of an introduction.

There are other examples of this throughout the gig. Her reading of Mr Lloyd’s reconstructed blues Sweet Georgia Bright, both in her initial introduction and then midway through after an intense plucked electric solo from John Abercrombie, has the acoustic piano coming on like a decision maker. Billy Hart trips his traps up a gear and Geri Allen plays a blues script as if it were her autobiography. The audience reacts accordingly; Ms Allen has nailed the whole thing. She has put purchase on her instrument so it speaks down the through the ages of what constitutes ‘blues in jazz’. It’s a subject all of its own, this performance could act as a byword to the art. The same could be said for any number of cuts on this live date. The Water Is Wide – ‘nu-gospel in jazz’, The Prayer – ‘meditation in jazz’; Geri Allen is at the crucible of these interpretations. Describing sound is ultimately the same as painting air, possible certainly, but no substitute for listening. On Live In Montreal, Geri Allen’s presence is not just about solos, there’s a bigger picture. How she feeds the metaphysical fire, gracing harmonies, the inflection, the rhythmic glance across bass and drums, the intros and outros. Jason Moran took over the piano position in the Charles Lloyd band. Stylistically he is a different gravitas, but even an exceptional pianist such as he undoubtedly is, finds himself having to draw on the blueprint Geri Allen left behind.

Charles Lloyd (tenor saxophone, flute), Geri Allen (piano), John Abercrombie (guitar), Marc Johnson (bass), Billy Hart (drums)

in concert, Montreal, 2001.

Geri Allen’s music got to me. In her portfolio I hear soul stirrers and Motown, practice my own doubt, celebrate dissonance, I can go to both Bud Powell’s Dance Of The Infidels and back to my old vinyl copy of Mary Lou Williams’ Black Christ Of The Andes, then move into M-Base territory. And I can bathe in the depths of the piano trio. All the way from Bill Evans’ Witchcraft to Cecil Taylor’s Nefertetti (who will surely come) and then return to Geri Allen’s own recordings with Charlie Haden and Paul Motian - which is where I came in. For sure, Geri Allen was a true maestro.

Steve Day www.stevedaywordsandmusic.co.uk

Visit some of our other Full Focus pages:

Steve Day - The Hot Spot

Sam Braysher - Braysher On Bird

Tori Freestone - My Lagan Love / In The Chophouse

Gebhard Ullman - Ta Lam